[edit]

Economic Aspects of the COVID-19 Crisis in the UK

This paper has drawn on evidence available up to 10 August 2020. Further evidence on this topic is constantly published and DELVE will continue to develop this report as it becomes available. This independent overview of the science has been provided in good faith by subject experts. DELVE and the Royal Society accept no legal liability for decisions made based on this evidence.

Summary

The coming months will bring new challenges for the economy and public health, as winter brings with it the risk of a second wave of infections and, over the longer term, changing patterns of local and national lockdowns become a ‘new normal’. Tackling these challenges will require targeted policies that are sensitive both to the spread of the disease and the economic costs of different interventions.

To help policymakers tackle these challenges we have drawn on insights from recent economic work into the pandemic that transcends the crude ‘health versus the economy’ dichotomy that indiscriminate lockdown measures tend to invoke, and instead seeks to explore more targeted interventions that have the potential to alleviate the trade-off between lives and livelihoods, attaining more desirable outcomes in both dimensions. We suggest methodologies including how economic models can incorporate insights from epidemiology; we review evidence about pandemic economic impacts; we suggest tools and methods that will be useful in monitoring the economy as it attempts to recover; and we suggest data required for conducting economic analysis.

By combining economic and epidemiological data to model different scenarios, policymakers can seek to tailor interventions to sectors and firms in ways that help to mitigate the risks of both a second peak and the looming prospect of a double dip recession. These ‘smart’ non-pharmaceutical interventions would recognise that sectors, firms and individuals are interlinked, with measures taken in one sector likely to affect other parts of the economy; that fear of contracting the virus – or uncertainty about how to manage it – are strong drivers of economic behaviour, meaning continuing anxiety will likely affect consumer confidence; that the prospects for an effective vaccine are uncertain; and that the extent to which infection leads to immunity remains poorly understood, creating a need for non-pharmaceutical interventions that may need to persist long-term. They may include:

-

Workplace rotation schemes: Rotations or split shifts have an exponential impact on infection rates, for example having just two cohorts or rotations within a workplace.

-

Subsidised workplace testing: Test-Track-Isolate (TTI) could help identify and control workplace outbreaks quickly, particularly in key sectors and those occupations in which ‘high-contact’ is a feature.

-

Flexible furloughing: A more flexible furlough scheme could help to open up the labour market and incentivise business investment in new home-working technologies. With the possibility of continued economic disruption in 2021 and beyond, there is a need to develop effective job-creation schemes in occupations and firms that can adapt to these new circumstances.

-

Sick pay: Current sick pay arrangements create a financial disincentive to self-isolate, with half of workers continuing to work through mild coronavirus symptoms, which in turn makes it more difficult to control transmission. Reviewing statutory sick pay could help incentivise those with symptoms to self-isolate.

-

Reopening schools: Schools can prepare for potential future resurgence of the epidemic with rotation schemes and better online provision for teaching and examinations.

-

Capitalising on government commitments to net zero and addressing regional inequalities: The government before the crisis had committed to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and to ‘level up’ the economy. A recovery plan could seek to progress these agendas. For example, promoting employment schemes supported by training programs in clean energy sectors and home insulation can aid in reducing carbon emissions.

-

Unemployment support: As the furlough scheme unwinds, it may be beneficial to review the design of unemployment support systems and schemes designed to help individuals back into work.

Such interventions must be carefully designed to account for the uneven distribution of the economic effects of the pandemic, as there are already indicators that impact of the pandemic on household finances and job prospects have been regressive. There is evidence to suggest that women have been harder hit economically by the pandemic and have picked up a higher proportion of extra caring responsibilities. Richer households have seen greater falls in consumption, and increases in savings, while lower-earning households have increased their borrowing to fund essential spending. Low-earning workers are also in jobs that tend to be harder to perform remotely, increasing their risk of unemployment or infection in the workplace, if mitigating steps are not taken.

Designing sound policy – and effectively tailoring it to ensure maximum impact – requires access to high-quality data. Those developing and monitoring the implementation of economic interventions would benefit from access to a range of different data types, including data relating to transmission of COVID-19, use of public transport, consumer spending and financial transactions. Many useful indicators of the economy’s response to COVID-19 could be found in data typically held by private financial institutions and are generally considered to have commercial value. While some progress has been made in making such data available, the UK lags behind its European counterparts in its ability to mobilise this data to develop policy responses, and action is needed by government to ensure fine-grained financial data is made available for such analysis.

This report illustrates some of the important economic issues that have arisen during the COVID-19 crisis in the UK. The complexity and changeability and the current economic environment mean the report is by necessity incomplete in its representation of the literature; it instead synthesises insights from four key areas that will be central to developing policy responses. First, it considers how economic models need to take into account insights from epidemiology, if these are to provide useful policy insights. Second, it reviews evidence about the impact of COVID-19 on the economy. Third, it explores the tools and methods that will be useful in monitoring the economy over the coming months as recovery is attempted from the economic shock caused by the pandemic. Fourth, it considers the data needed for conducting economic analysis, calling for further access to data in key areas.

Citation

(2020), Economic Aspects of the COVID-19 Crisis in the UK. DELVE Report No. 5. Published 14 August 2020. Available from https://rs-delve.github.io/reports/2020/08/14/economic-aspects-of-the-covid19-crisis-in-the-uk.html [pdf].

Table of Contents

- Key Conclusions

- Introduction

- An Integrated Evaluation of the Health and Economic Consequences of Lockdown Measures and Reopening Strategies

- Tracking the Impact of Economic Shocks in Real-Time Transaction Data

- Designing Targeted Interventions: Some Guiding Principles

- Supply-Chains Under Lockdown: Assessing Costs and Designing Targeted Interventions

- Trade-offs Between Economic and Health Risks When Considering the Lockdown Release Date

- The Pandemic and the Labour Market

- Economic Issues in Physical Distancing

- Workforce Rotation Within an Organisation: A Micro-Strategy to Shift the Policy Frontier Upwards

- Planning for the Possibility of Waning Immunity

- References

- Footnotes

Key Conclusions

A tight lockdown that is released too quickly or too fully would probably lead to adverse outcomes in terms of both lives and livelihoods. To be precise, too quickly or too fully here means relaxing the lockdown without sufficient regard for the state of the pandemic, the capacity of the health care system, and epidemiological markers such as the effective reproduction number. The rationale is simple: an abrupt and premature lockdown exit would lead to a second wave of infections that would bring with it both a higher death toll and additional costs for the economy. Through the lens of integrated macroeconomic and epidemiological models, there are other policy options that are probably preferable to an abrupt lockdown exit, for example coupling such a cautious lockdown exit strategy with other targeted approaches, such as work rotation, and TTI schemes.

Policy needs to be flexible enough to adjust to uncertainties, in particular, about the future evolution of the epidemic. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, smart policy in many cases should be dependent on the state of the epidemic and the economy and, in particular, change if epidemic and economic markers cross certain thresholds. For example, labour market strategy should be sensitive to the persistence of the crisis and the likelihood of further waves of infection. Further action is also needed to ensure that policy responses account for the regressive impact of the pandemic on household finances and job prospects, and the distributional implications of different approaches to managing the pandemic.

Data access will be vital to developing policy responses. The UK government and supporting bodies should continue pursuing the goal of obtaining more and more representative and fine-grained transactions data from UK financial institutions for the purpose of monitoring the impact of COVID-19 and associated policy interventions. Such data are valuable assets in the current situation, and the UK should be the vanguard in efforts to harness its power for effective and timely policymaking.

Models for studying the impact of pandemics need to recognise that measures taken in one sector affect other parts of the economy as sectors of the economy and firms within a sector are interlinked. Not recognising these risks gives a misleading picture of the economic costs of restricting some kinds of economic activities. For example, extreme lockdowns have severe economic consequences for non-essential sectors, such as hospitality, sports, and leisure, which are also large employment sectors.

Given the nature of supply chains spanning the entire world, the effectiveness of the existing UK strategy will depend on the policies that other countries implement, in particular, those that are tightly connected to UK in the production process and consumption. The current crisis has brought to the forefront the need to monitor and design supply chains that are responsive to shocks, for example by understanding which firms are essential for meeting demand of key goods and services in a crisis. Answers to these questions require substantially more granular data.

Any economic analysis rests on the assumptions that we make about the properties of the disease. Thus, any policy prescriptions must also be understood in the context of what we currently know about the basic immunological facts of COVID-19 and that are sensitive to the duration of the shock and to the evolving understanding of the nature of acquired immunity. Policies should ideally be able to adjust to uncertainties and work whether immunity is acquired indefinitely or is temporary. As new understandings of the continuing effects of COVID-19 infection emerge, policy responses may also need to be adjusted take into account the impact of the virus on the long-term health of individuals.

Introduction

The Economic Impact of the Pandemic on Households and Firms

There are many ways of tracking the economic impact of the pandemic:

-

At a household level, there are impacts on consumption and earnings. In analysing these, it is important not to neglect within-household changes with shifts in caring responsibilities across parents.

-

The behaviour of firms, which make key decisions on employment and investment, is also important. This will be affected by a number of different factors, including:

-

Following the crisis, space management will become a particular challenge as will be new concerns around workplace safety, e.g. making sure that workers have appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

-

There will be a need for rapid response and outbreak control in the event of a cluster–leading to shut down of individual businesses in some cases.

-

The abrupt changes in revenues have necessitated rescheduling of obligations such as paying taxes and rent. But many firms will also have resorted to taking out loans (many of them guaranteed by the UK government) which will, in time, have to be paid off, rescheduled, or forgiven.

-

Some of these adjustments by firms and households require fundamental behavioural changes against a backdrop of high levels of uncertainty about the magnitude and duration of the disruption that they face. Just what will become the “new normal” for the economy is far from clear. Those who operate in the market economy will see a range of wage and price adjustments; many more workers will probably be asked to take pay cuts and some prices will have to increase to fund the additional costs of doing business. Supply chains and production networks create an interdependent process where changes in one part of the economy influence others. Some sectors of the economy are more dependent on public funding and regulated pricing. Some pre-crisis business models will no longer be viable, as we have seen in public transport, which will require either changes in frequency, fares, or public funding.

How all of this plays out will determine the size and duration of the economic adjustments needed. The whole adjustment process, whether in markets or the public sector, will be greatly affected by government policy, both directly and indirectly.

Uncertainties, Behaviour, and Inequalities

Understanding the impact of the crisis on the economy requires analysing the incentives and disincentives that firms and households face. Some of these are material incentives due to changes in financial costs and benefits from different actions, but non-material considerations are crucial too with psychological costs due to the fear of infection.

Developing such understanding of individual responses is challenging. How far people are able to make consistent judgements in such circumstances is an open question and the behavioural economics literature has identified a range of behavioural “biases” that can inform an individual’s response. An important issue is also how far economic responses are best captured by assuming that they are based on self-interest. Physical distancing and mask-wearing/face-covering are partly protective to the individual taking the action, but also pro-social. A range of existing studies in economics have found predictors of pro-social behaviour (such as education) that are likely to be relevant. That said, the impact on psychology and non-material factors is often much more difficult to assess, especially when the context is novel and full of uncertainties. For example, the kind of people who answer economics survey questions during a pandemic, as well as their answers, are subject to potential biases, making it hard to obtain representative and unbiased reports on behaviour.

Restrictions that affect the economy are likely to remain in place for some time and will be subject to change, sometimes at short notice, in response to changes in the epidemiology of COVID-19. In aggregate terms, these restrictions will be manifested in lower Gross Domestic Product (GDP). But looking at things purely in aggregate terms is limiting. It is crucial to study who is losing (and in a few cases gaining) from the crisis. Those in secure employment who can easily adapt to working from home and have few caring responsibilities are likely to have suffered least both financially and in terms of their overall well-being. Those who face the prospect of unemployment, living in cramped conditions, and have had disruption due to the need to act as carers or educators will tend to have suffered the most. Changes in aggregate income do not tell this story. Nor does looking at aggregate income changes tell us about what is going on–the way in which key decisions are being affected by the crisis nor how businesses are adapting or changing.

Although the crisis is unique, the main forces that are driving the economy can be measured using standard features of economic analysis with the outlook for the economy dependent on forward looking behaviour of government, consumers, and businesses. The duration and intensity of the economic effects, particularly those involving investments, will be affected by confidence in the future. It is critical to understand how behaviour is changing due to the way in which citizens are experiencing the crisis and assessing the dangers posed by the progression of the disease. This affects both the need for policy intervention and the nature of these interventions.

If consumers believe that they need to save in anticipation of a worse future, this may reduce consumption and investment today, and can make such beliefs self-fulfilling. This also depends on what people expect government to do, in particular, the duration of support measures and policies to stimulate the recovery. The fact that policy is so uncertain makes it extremely difficult to forecast the economy at the macro level and such forecasts need to be interpreted cautiously given extreme levels of uncertainty. But this matters at the micro level too as those making economic decisions have their concerns about particular features of the economy. There is now a large literature in economics that shows that uncertainty has a significant impact on forward looking behaviour and that this is particularly important when there are large adjustment costs such as due to physical distancing measures.

The Trade-off between Lives and Livelihoods

One of the core questions raised by the crisis is whether and to what extent there is a trade-off between saving lives and preserving livelihoods. Figure 1 lays out a concept that has become central to economic thinking about the crisis, the idea of a policy frontier, which is discussed further below. It embodies three core ideas. First, different courses of action (for example, how severe the impact of restrictions in place is on economy activities) give rise to different paths of progression for the disease and the economy, affecting both health and economic costs. Second, indiscriminate lockdown measures likely create a trade-off between the two, with more severe restrictions being better for public health but worse for economic welfare–though knowing the precise terms of that trade-off is very difficult given challenges in measuring and predicting both the economic and epidemiological consequences of a given policy. Third, more targeted interventions have the potential to alleviate the trade-off between lives and livelihoods and to shift out this policy frontier, thereby attaining more desirable outcomes in both dimensions.

An emerging field called epi-macro, which combines dynamic models from epidemiology and macroeconomics to study the joint path of disease and the economy, is being developed in response to the crisis for exploring these issues in quantitative models. How far these models will be able to inform specific policy paths taken by government is still an open question, but they are already proving important in framing the logic of trade-offs faced in managing the pandemic. These epi-macro models require those who are taking decisions to confront the issue of balancing economic costs and public health benefits. Such models can also address the distributional implications of different strategies, particularly those that will affect workers in different sectors of the economy.

The epi-macro models also focus attention on the search for policies that can deliver health benefits at low economic costs, such as wearing face masks/coverings, as well as the importance of avoiding those policies that could stimulate economic activity but encourage risky behaviour, such as subsidising eating out. Such models do not give definitive answers but are important for policymaking.

More controversial is whether economic analysis can also provide a way of helping to resolve how the trade-off between lives and livelihoods can be made. There is a well-developed economic approach, which has been influential in the public health systems, that looks at the impact of treatments in terms of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYS). In parts of the UK, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has used such methods of evaluation before the crisis to decide on whether to support a particular health treatment or certain drugs. We discuss pros and cons of using this approach in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic below and report on some recent analysis that has tried to quantify the trade-off between loss of income and lives lost. When conducting such analyses, it is important to keep in mind that much of the economic cost may not be attributable to the policy. There is also no attempt to look at the distributional effects across any dimensions such as old versus young or across different regions. How large are the long-term impacts on physical and mental health is also an issue, although they would tend to suggest, if anything, that looking at short term QALYs is an underestimate of the true societal cost.

The Way Forward

Policymakers must plan responses that manage the impact of COVID-19 on the economy over the longer term

When designing policy, it is important to have a realistic expectation for the future. The virus is likely to become endemic, and to recur in spikes, which may be either sporadic, seasonal (winter), or both, and it is still uncertain whether and when an effective vaccine will be made. Even if a vaccine is effective, it may need to be re-administered at intervals of 1 to 3 years, to boost waning immunity. And there will be significant logistical challenges and possibly political challenges in the manufacture, distribution, and administration of a vaccine. Hence, although it is hoped that a vaccine will control the infection, it is unlikely that it can eradicate it. It is important therefore not to invest all hope for progress only in a vaccine; developing drug treatments is also important. This underpins the need to develop economic analysis to support policy that works over an extended period of time. Moreover, since anxiety over COVID-19 adds to the impact of lockdown on the economy, it is likely to take some time to dispel this anxiety even if a vaccine or drugs are available, as evidenced by the slow return to work in many places where the lockdown has been lifted.

Bespoke survey data will provide a useful way of learning about how behaviour is responding to developments in the progression of the disease, and there is also scope for designing field experiments that give insights into economic behaviour. Given the high degree of uncertainty and the psychological responses to the virus, there is value in understanding how messaging matters alongside more conventional incentives.

There is a pressing need for high-quality data to be made accessible for policy development and monitoring

Designing sound policy analysis requires good data. One of the novel characteristics of the COVID-19 crisis is the swiftness of developments occurring in the economy that require more than just the existing conventional ways for measuring their impact. Financial transactions data is one such option that provides a way of looking into individual spending decisions on a day-to-day basis, but these data are typically held by private financial institutions. This presents a challenge since such data are often of commercial value. There has been some success in making such data available, but there are a lot of data that are not available to researchers and policy analysts. Below, we review what has been learned by studying such data and we note that many other countries have much better data accessibility than the UK. We would highlight data availability as a significant challenge for the UK. We strongly recommend for UK to strive to make more fine-grained datasets available by mandating their release from the private firms and other parties involved.

Responses implemented in the last five months will have a continuing legacy that will need to be managed

The scale and speed of measures taken to combat COVID-19 have had a heavy toll on the economy–one that is likely to last for years. Of particular concern is the impact of the economic shock on employment as businesses shed workers, which may accelerate further as the furlough program is wound down. Unemployment is a personal and familial challenge for those who are directly affected, but it also creates challenges for maintaining societal cohesiveness as inequality widens.

Although some important issues are covered, this report is not a complete description of all dimensions of the economic impact of COVID-19. For example, one feature of the crisis has been to support businesses through emergency loan facilities. This will create a legacy that weigh on the employment and investment decisions of firms, and also potentially affect the behaviour of lenders going forward. The fact that these loans are guaranteed by the UK government implies that dealing with this legacy is a kind of industrial policy on how to manage exposures in different firms and sectors of the economy. It is also important to understand supply and demand constraints. Even if the economy is opened, many activities may be curtailed by individuals who still perceive significant risks associated with some economic activities. Understanding these factors in a granular way is still a work in progress.

A lot of useful economic analysis works by specifying targets and then looking at the most economical and efficient ways of attaining these. Thus, we have targets for reducing child poverty or limiting carbon emissions that serve as a useful focal point for considering the value of alternative policies.1 This approach is potentially powerful in trying to limit the spread of COVID-19. Moreover, the ability to react to uncertainties is important, i.e. considering whether there are some policies that are less contingent on specific knowledge that we do not have; the case for wearing face masks/coverings is an example here.

Continued support will be necessary, and could be aligned with longer-term strategic priorities

The UK government has been supporting the economy throughout the crisis. It is important to continue this support in a strategically informed way by focusing on policies that deliver economic benefits, while minimising the risks of increasing transmission of COVID-19. There is still an active learning process about the best way to do this. In a period of crisis, there are opportunities to develop new policy directions, and businesses can learn how to respond to these. The government before the crisis had committed to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and to ‘level up’ the economy, in particular, addressing the UK’s long-standing regional inequalities. There will be opportunities to pursue these agendas as part of the recovery plan. For example, promoting employment schemes supported by training programs in clean energy sectors and home insulation can aid in reducing carbon emissions.

Given the significant increase in unemployment, especially among the young whose economic prospects are most severely hit by the crisis, unemployment will need to be extensively studied, as has been done for past recessions. Supportive policy requires a strategic approach informed by data, and finding means to invest a significant share of GDP in clean energy and new transportation networks is important.

1. An Integrated Evaluation of the Health and Economic Consequences of Lockdown Measures and Reopening Strategies

There are a number of possible conceptual frameworks for jointly evaluating the economic and health consequences of lockdown measures. These include in particular Green-Book-type cost-benefit analyses. Much of recent economics research has, however, taken a different approach to evaluating government measures in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, namely to quantify and visualise different policy alternatives as tracing out a “policy frontier.”2 Figure 1 plots an illustrative example of such a frontier (see left panel).

Figure 1: Example policy frontier for integrated evaluation of health and economic consequences of lockdown measures (Left). Targeted measures such as TTI can shift out the policy frontier (Right).

Each policy alternative is evaluated in terms of two success metrics: saving lives and preserving livelihoods or, more precisely, a measure of constituents’ economic welfare. As an example, a tight and prolonged lockdown may save many lives in the short term but comes with a large welfare cost, whereas an extreme policy of no public health intervention may cost many more lives in the short term but may result in a relatively temporary recession and less severe economic costs. At the same time, the example frontier is upward sloping in the vicinity of the “do nothing” point, indicating that some form of intervention may both save more lives and preserve more livelihoods.3 An important advantage of the frontier approach vis-à-vis a traditional cost-benefit analysis is that, while it quantifies the consequences of different policy alternatives, it stops short of putting a particular monetary value on life.4 It instead presents policymakers with a menu of policy options that may all be acceptable depending on different evaluations of such tradeoffs. It therefore explicitly recognises that balancing tradeoffs between lives and livelihoods is ultimately a political decision driven by many considerations including ethical ones. At the same time, the frontier approach nevertheless identifies suboptimal policy options that are dominated by others (those inside the frontier and on the upward-sloping part).

The frontier approach also suggests that we should aim to find policy interventions that shift out this frontier in the sense of both saving more lives and preserving more livelihoods (see the right panel of Figure 1). This is because such interventions are desirable independently of subjective evaluations of the tradeoff between these. As we discuss below, targeted lockdown measures and reopening strategies can achieve precisely this goal. Finally, it is important that the metric for economic success is a measure of people’s welfare and not aggregate income (GDP). One important reason (though not the only one) is that, as we also discuss in Section 6 below, the costs and benefits of lockdown appear to be very unevenly distributed. Measures of economic welfare take into account such distributional effects while GDP does not.

An emerging field called epi-macro, which combines dynamic models from epidemiology and macroeconomics to study the joint path of disease and the economy, is being developed in response to the crisis for exploring potential trade-offs between saving lives and preserving welfare in quantitative models. A typical model marries a standard macroeconomic model of household and firm behaviour with a simple epidemiological model, typically a compartmental model such as an SIR or an SEIR model.5 Both parts are then disciplined with data on the evolution of the epidemic and the economy, e.g. of the type presented in Section 2. Such an integrated approach is important to capture the two-way feedback between infections and economic activity and the potentially complicated non-linear dynamics of both the economy and the epidemic.

Some economists have considered the possibility of formally trying to assess the trade-off between lives and livelihoods based on valuing life.6 In effect, this is putting a value on human life to try to achieve some kind of consistency in the decision-making process and to assess the relative desirability of different points on the frontier in Figure 1. It corresponds to a broadly utilitarian philosophy where costs and benefits can be added. In principle, this approach provides a way of trading off economic losses and lives saved, by putting them on a comparable metric, i.e. money. Such methods were in part a reaction to what were deemed arbitrary and inconsistent judgements being made over treatments. And they are easier to apply to well-defined trade-offs and to rationalise the allocation of resources within a spending envelope rather than trying to decide how much to spend on health compared to other forms of public spending or whether to raise taxation to spend more on health care.

However, the trade-offs in the case of COVID-19 are not yet well understood; we don’t really understand the impact on $R$, or the impact on the economy in the short term, let alone the medium or long term impact on economy and the secondary impact on health/welfare. There are good reasons to think that there are vast inconsistencies in welfare judgements across a wider range of policy decisions, particularly those involving life and death. There is no effort to look at whether more should be spent on road safety, airline safety, or saving malnourished children in low income countries. A QALYs-based approach could be used to inform this. But these decisions also depend on psychological responses to different forms of death and even the way that these are framed by the media. And arguably, one key role of the political process is to make politicians accountable for making these judgements, instead of believing that these things are amenable to scientific judgement.

Some recent analysis has tried to quantify the trade-off between loss of income and lives lost. Such exercises have suggested that putting large values on life in excess of those that are used in making assessments between alternative treatments suggests that the costs of the lockdown strategy are in excess of the benefits. Indeed, in their central case, where GDP falls by 15%, 440,000 lives are saved and each life is assumed to be worth five more QALYs valued at £30,000, and people are expected to live on average for five more years, then the loss in monetary terms is around £250 billion. However, as we have stressed already, much of the economic cost may not be attributable to the policy. There is also no attempt to look at the distributional effects. How large are the long term impacts on physical and mental health is also an issue, although they would tend to suggest, if anything, that looking at short term QALYs is an underestimate of the true societal cost.

Even if the idea of assessing trade-offs in this way is unattractive in simple terms, many would find such exercises useful as one way of informing economic policy. And it does open up the important question that there is a trade-off that needs to be confronted and that lives saved is not the only way of assessing success and failure as the economic cost incurred in doing so also matters. But such methods have their limitations. For example, nobody would seriously propose using monetary valuation methods for the decision to go to war or whether to use capital punishment, and it is not only because it is difficult to give monetary values, but because important issues of principle are at stake.

2. Tracking the Impact of Economic Shocks in Real-Time Transaction Data

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic has led to the rapid development of an empirical literature in economics that uses individual financial transactions made by households and firms to track the impact of spread of virus, lockdown, and other government policies. The sources of such data include financial applications on mobile phones, payments systems operators, and traditional banks. Datasets vary in the exact information they provide, but they generally provide a high-frequency measure of household purchases, firm sales, and information on individual characteristics. In this note, we describe some advantages of such data and initial findings from a study of UK payments data, and we argue for an expanded effort for data collection in the UK, which up to now lags behind other major economies such as US in the availability of financial transaction data for policy analysis.

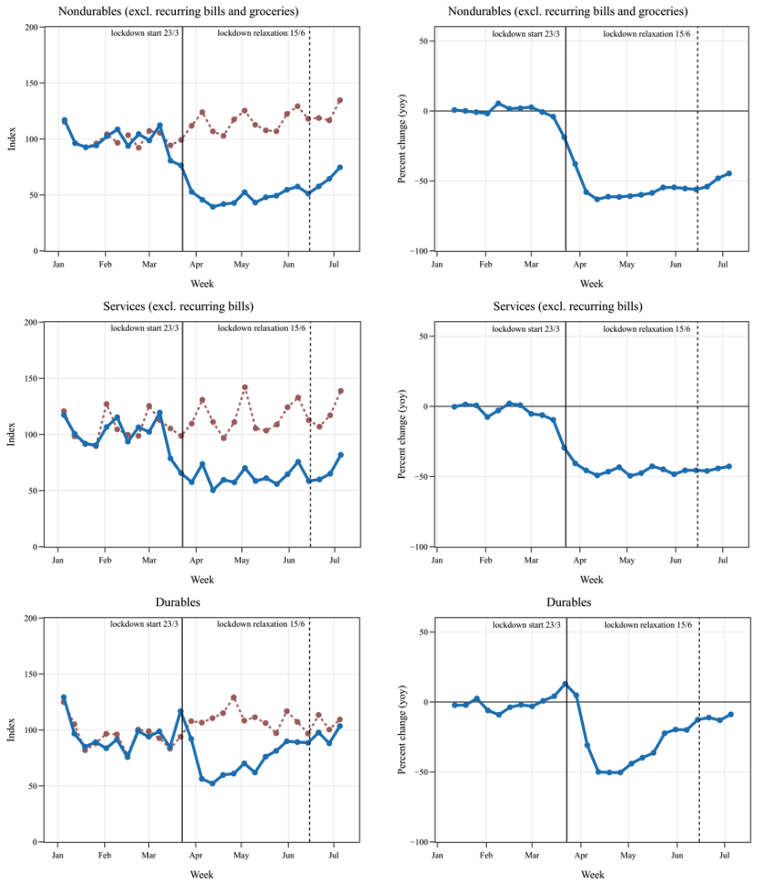

A major advantage of payments data is its timeliness.7 Unlike official national statistics, which often take months to compile, financial transactions provide a near real-time account of economic activity. This is a particularly important policy tool when the economy is in crisis; it can support evidence-based timely policy responses to major economic shocks. In Figure 2, we illustrate this by reporting the year-on-year growth in weekly discretionary consumer spending across different sectors in the U.K. from 1 January to 5 July 2020. This chart comes from Hacioglu, Kaenzig, and Surico (2020b), which analyses high-quality data on approximately 15,000 users of a financial app (Money DashBoard). The vertical lines indicate the start (on 23 March) and the relaxation (on 15 June) of the lockdown measures.

Figure 2: Average weekly spending in various sectors normalised to 100 in January (left); and year-on-year changes (right). Red line refers to 2019 and blue line to 2020.

First, we can see that in line with the health system effects, the largest decline in expenditure appears to have occurred during the second week of March 2020 (when WHO announced the pandemic) and so earlier than the introduction of either physical distancing policies (on March 16) or lockdown measures (on March 23). Second, during May and June–where the last two weeks have been characterised by some initial and further easing of the lockdown measures respectively–consumer spending has started to recover somewhat (especially retail, not reported in this note), though the recovery in discretionary spending until 5 July is still subdued.8 Third, the recovery has been quite heterogeneous: durables goods and services sectors have recovered fully or partially, but others such as restaurant and entertainment in services have not. The results on both the introduction of the lockdown and its partial easing suggest that fears and uncertainty may be also holding back consumption, over and above any direct effect due to the lockdown per se.

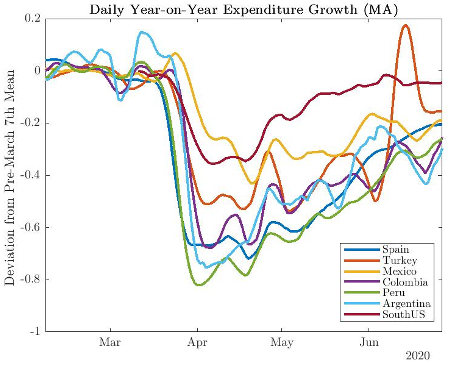

Also consistent with this, research has found that consumer expenditure fell nearly as much in Sweden, where there has not been a complete lockdown, as it did in Denmark, where there has been a complete lockdown (see Figure 3, left panel, based on Andersen, Hansen, Johannesen, and Sheridan (2020)). Analysis of Google Mobility data9 finds similar patterns for workplace mobility (Resolution Foundation (2020)). Finally, researchers have examined data from South Korea, which did not implement a lockdown and has instead relied on testing and contact tracing; they found that localised outbreaks led to large drops in local employment (Aum, Lee, and Shin (2020)). To complete the international comparisons, the right panel of Figure 3 plots expenditure growth across seven countries based on Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) card data from Carvalho et al. (2020). After a sudden, abrupt fall in spending throughout the world in March, one observes a notable recovery in consumer spending in most economies.

Figure 3. Consumer expenditure in the international economy.

An additional advantage of payments data is its granularity. This allows one to measure which firms and households are most affected by economic shocks, which is where many of the most relevant policy questions lie. For example, one can determine which sectors and regions are hardest hit by lockdown, and design fiscal stimulus accordingly. There is increasing evidence from the transaction data that more affluent households have cut spending by more than others. Figure 4 illustrates this point using two separate data series. The left panel, from Hacioglu, Kaenzig, and Surico (2020b), shows that UK households in the top quartile of the labour income distribution have cut spending proportionally the most during lockdown. The right panel, from Carvalho et al. (2020), shows that households residing in the upper quintile of Madrid’s zip-codes by income per capita have also adjusted most strongly. These observations are also supported by research from the US (Chetty et al. (2020), Cox et al. (2020)).

Figure 4: Year-on-year growth in discretionary spending by income levels (UK left, Spain right)

Moreover, as confirmed by Figure 5 below, the UK data reveal that more affluent households have increased substantially their savings during the lockdown by cutting non-essential spending on categories such as restaurants, hospitality, recreation and culture, and travelling. On the other hand, low-earning families (depicted as red line in Figure 4) have increased their borrowing to fund spending on essential consumption such as groceries, food, and utility bills.

Figure 5: Decline in earnings, income and expenditure in June 2020 relative to June 2019 across different incomes groups.

Figure 5 shows that the decline in earnings exceeds the decline in expenditure only for users at the very bottom of the income distribution in UK. For all other groups, the pandemic shock is associated with a significant positive gap between the decline in earnings and the decline in spending, which is increasing in the level of income. On the other hand, looking at the orange bars reveals that users with after-tax income below £20,000 have faced a fall in income that is smaller than the fall in their spending. It should be noted, however, that the change in personal saving rates implied by the gap between the drop in income and the drop in spending for this group is smaller than for users with income in the range £20,000-30,000, and is only a fraction compared to the groups above the median income.

What have we learned from transaction data and what do they imply for the future?

The data shows important heterogeneity across income groups and also points towards the key role that uncertainty plays in consumption patterns. In particular, looking at granular financial transaction data for a large number of users at weekly frequency suggests that the decline in UK consumer spending is driven by high-powered/high-earning affluent households. These families are cutting non-essential consumption as a result of both the restrictive measures in place and the health and economic crisis more generally. Furthermore, in the UK, the largest drop in retail, restaurant, and transport spending started well before the lockdown was introduced, suggesting that one should be cautious in believing that reopening the economy can regain the level of confidence and thus spending to the level seen before the crisis.

In terms of economic policies to support the economy, the joint analysis of spending and income allowed by financial transaction data suggests that measures to stimulate consumption have to channel the increased savings by top earners back into spending. This is because many low-earners are employed by those very sectors–such as restaurant, recreation, hospitality, etc.–in which high-earning households have cut most of their spending. Measures that are effective in doing this, resulting in higher spending in retail, restaurant, hospitality, recreation, etc. will also support salaries at the bottom of the income distribution, thereby feeding back into aggregate demand through a multiplier effect. However, what measures would be effective in doing this is moot. There could be scope, for example, for targeted VAT cuts towards these sectors but the modalities for this or other stimulus measures require a more detailed analysis.

What data and monitoring should be put in place for the future?

The financial transaction data used so far to analyse UK spending patterns has provided valuable insights, and Hacioglu, Kaenzig, and Surico (2020a) have shown that the time series of aggregate consumption constructed with a bottom-up approach from this transaction data has a correlation of 0.79 with the time series of household expenditure on final consumption available from the national accounts. But several other countries have transaction datasets whose sample sizes are far greater than those provided by the financial apps, and which also contain millions of users and billions of transactions (see additional readings below). Such datasets come close to providing a real-time snapshot of spending in the entire economy, and arguably contain a more representative sample of consumers across age, occupation, and income groups, thereby making them even more appropriate for macroeconomic policy analysis. These datasets can also be used to understand very detailed patterns, such as postcode-level spending dynamics and their relation to disease incidence (Carvalho et al. (2020)).

Our recommendation is for the UK government and supporting bodies to continue pursuing one of the most important and urgent goals of obtaining more and more representative and fine-grained transactions data from UK financial institutions for the purpose of monitoring the impact of COVID-19 and associated policy interventions. Such data are valuable assets in the current situation, and the UK should be the vanguard in efforts to harness its power for effective and timely policymaking.

3. Designing Targeted Interventions: Some Guiding Principles

As already mentioned in Section 1, targeted policies have the potential to deliver superior outcomes in terms of both health and economic outcomes. In terms of the policy frontier in Figure 1, such “smart” policies may be able to alleviate the tradeoff between saving lives and preserving livelihoods, thereby shifting out this frontier. Smart policies can take multiple forms, including non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) or fiscal policies targeted at particular sectors, firms, or individuals. Here we briefly discuss a few guiding principles for designing such targeted interventions. Sections 4 and 8 make particular suggestions for what such targeted interventions could look like in practice.10

The first guiding principle follows directly from the idea that policies are “smart” if they do well in terms of both the metrics for evaluating policies described in Figure 1, i.e. saving lives and preserving constituents’ economic welfare. To deliver on these two objectives, the two-by-two matrix in Figure 6 provides a guide for policymakers aiming to identify desirable targeted policies. It describes an adapted and simplified version of the “reopening index” of Baqaee, Farhi, Mina, and Stock (2020). The basic idea is to categorise each policy in terms of its marginal effect on (i) economic welfare (the different rows) and on (ii) infection risk, as measured by the effective reproduction number $R_t$ (the different columns).11

Figure 6: Policies in the green top-right box are desirable whereas those in the red bottom-left box are undesirable.

In this idealised case in the figure above, only four different cases are possible based on whether the policy under consideration has high or low marginal effects on these two metrics. Smart targeted policies are those in the green top right box: they yield a large marginal welfare gain but with only a small marginal increase in $R_t$; or a large marginal reduction in infection risk, i.e. a large negative marginal $R_t$ but at only a small welfare cost. Conversely, undesirable policies are those in the red bottom-left box: these yield only a small marginal welfare gain but come with a high marginal infection risk; or they yield only a small marginal reduction in $R_t$ but at a high welfare cost. Finally, if a policy ends up in one of the remaining two boxes (top left or bottom right), the case for or against it is less clear cut. Acceptability to the population and feasibility are, of course, also important: there is no point in pursuing a policy that is too complex to be likely to succeed or is too unpopular.

Some simple examples help illustrate the use of the matrix and how some existing policies may be classified. These should be viewed as illustrative; more empirical evidence and a more thorough evaluation of the risks and benefits of these activities is needed. First, virtually all countries hit by the COVID-19 pandemic have banned large indoor events, e.g. large indoor sporting events or large nightclubs. In terms of the matrix in Figure 6, this should most likely be viewed as a desirable policy in the green top-right box. The risk of these events serving as superspreading events means that banning them probably comes with a large reduction in the effective reproduction number $R_t$;12 at the same time the impact on constituents’ economic welfare is comparably modest. Two other examples falling into the top-right box of desirable measures are likely: (i) the government’s guidance during the lockdown exit advising people to “work from home if you can” and (ii) mandatory face masks/coverings in shops–both bring with them potentially sizable reductions in $R_t$ but relatively low economic cost. In contrast, consider a policy of subsidising eating out. Such a policy is more problematic because it brings with it an increased infection risk, i.e. a potentially high marginal $R_t$. It would therefore likely fall into either the top left or bottom left box.13

A second guiding principle, one that applies to all economic policymaking, is the so-called targeting principle: policies should aim to target specific externalities or frictions. In the absence of a clear rationale for a policy in the form of such “market imperfections”, it may be better to not pursue this policy. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, one potentially important externality is an “infection externality” by which individuals probably underweigh the risk of infecting others and therefore engage in less voluntary physical distancing than would be epidemiologically optimal (see e.g. Farboodi, Jarosch, and Shimer (2020)). There are many other potential frictions and valid rationales for policy intervention, but for each policy, it is important to be clear about which ones a policy aims to target and also how it plans to achieve those ends.

A third guiding principle is that policy needs to be flexible enough to adjust to uncertainties, in particular, about the future evolution of the epidemic. In this regard, an important lesson from economic theory is that a policy that does well in environments with lots of uncertainty often features state dependence, meaning that policy is contingent on and changes with the realisations of uncertainty. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, smart policy in many cases should be dependent on the state of the epidemic and the economy and, in particular, change if epidemic and economic markers cross certain thresholds.

4. Supply-Chains Under Lockdown: Assessing Costs and Designing Targeted Interventions

Locking down a community and closing down economic activity in certain sectors is costly economically and those costs are not equally spread throughout the economy. For example, key production activities, such as textiles, chemicals, iron and steel, etc., that are more central in economy-wide supply chains have a much wider impact on the economy when idled. Further, even if these central production nodes are kept open during a lockdown, their scale of operations is likely to decrease as downstream activities like retail, which serve UK households directly, are kept shut, thereby limiting their demand for intermediate goods and services. Finally, employment declines in sectors under lockdown spill over to the rest of the economy via final demand, as households scale back consumption in face of job loss and income uncertainty.

The research on production networks provides a framework to organise these complex patterns of propagation of economic disruption under lockdown. It allows one to estimate and quantify the economic costs of a particular lockdown strategy, either already implemented or proposed. Further, it allows policymakers to discover optimal targeted lockdown strategies. Hence, it is an important input to policy now as we partially re-open the economy, and in the future, if further limited lockdowns are required.

A policymaker defining a lockdown strategy is solving a coupled contagion and production problem: finding which economic sectors to close to minimise damages to the economy while keeping down COVID-19 transmission. In particular, the partial reopening of some economic sectors increases labour mobility, thereby increasing contact rates–both while commuting to and in the workplace–and the likelihood of new local COVID-19 outbreaks. These effects would be dictated by the geographical distribution of employment in these sectors, commuting patterns, and the epidemiology of COVID-19 diffusion. The network perspective on production that we introduce here is a first step towards an integrated epi-production network framework, which could allow policymakers to achieve superior outcomes by pushing the possibility frontier outwards via targeting, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The framework in practice: lockdown costs and optimal interventions

In what follows we provide an example of how to apply this methodology.14 For a given policy experiment, we consider aggregate GDP as the economic outcome of interest, and we consider the total number of people commuting to work as a proxy for meeting rates. Implicitly, this assumes pure homogenous mixing in the diffusion process both across sectors and across space. This serves purely as an illustration. The ingestion of further data sources (e.g. spatial patterns of activity and commuting flows) and collaboration with epidemiologists will allow us to incorporate a more realistic diffusion process. We return to these considerations towards the end of this document.

In our representation of the UK economy, there are 54 sectors, all of which may trade with each other, hire workers, and produce outputs. Some sectors’ outputs are intermediate and other sectors produce final consumption goods that households can purchase. Households earn wages by supplying labour to different sectors in the economy. In the model’s equilibrium, the prices of all goods and the wages paid by each sector are such that supply and demand equate across the economy. Further, we input into the model sector-specific measures of both the amount of working from home possible and the proportion of parents with school age children, whose labour supply is affected by school closures.

As an illustration, we evaluate here the May 10th UK government policy announcement regarding lockdown easing.15 The main change of this announcement relative to the lockdown in place since the middle of March is that workers without school-age children, who worked in sectors not directly shut down by government policy, were actively encouraged to enter the labour force by travelling to work. Under this new policy scenario, we estimate that total output in the economy falls by nearly 24% relative to the pre-COVID situation. The number of people working will be 22 million, with roughly 8 million people out of work or furloughed, about 15 million workers being able to work from home and the remaining 7 million commuting to their workplace.16

We then explore alternative lockdown strategies that can help policymakers in designing more effective reopening strategies. Namely, we ask whether there is an alternative to the current policy scenarios that is superior in its GDP impact, while requiring a smaller amount of physical commuter flows and therefore lower contact rates. To do this, we search for the targeted network reopening that minimises GDP falls under the constraint that only 5 million people commute to work and a total of 15 million people working remotely from home. Compared to the May 10th scenario above, this scenario keeps the same number of workers working from home–but not necessarily distributed across the same sectors, while allowing for a slightly smaller number of people physically commuting to their workplace. We estimate that the optimal strategy leads to a fall in economic output by 18%. As such, the optimal targeted strategy pushes the policy frontier outwards by achieving both better GDP performance and smaller contact rate.

To understand why the network-targeted policy may offer a superior performance in resolving the coupled contagion and production problem, it is useful to compare it to the current, post-May 10th policy. The government policy is stark in its employment allocation: many sectors will be fully back to productive capacity, while some sectors are mandated to be closed. The first aspect of this policy generates substantial commuting flows, whereas full business closures continue to impose large economic costs, including constraining the demand for the outputs of sectors that are fully open.

An optimal targeting policy, instead, reduces the number of sectors that are fully open, targeting only those with greater direct and supply-chain impact on the economy. It also reduces the economic distortions associated with having some full-sector lockdowns, by prescribing partial lockdowns through part-time on-site working (supplemented by the maximum possible level of work from home). By doing so, the optimal targeting policy can deliver GDP outcomes improve on the implemented policy while requiring smaller commuting flows and lower contact rates.

Ongoing work and further considerations.

The framework described above relies on accurate measurements of the UK economy, combining information on sector-to-sector linkages and lockdown-specific data. Over the past two months, we have worked closely with the ONS to improve the data inputs into our model and are now in a position to refine our estimates further. One missing ingredient so far is information on the size of the furloughed workforce by sector that would allow us to better proxy for final demand forces.

We have also been able to source data on the geography of sectoral employment across the UK, together with the associated commuting and return to work patterns. This opens up the possibility of coupling our production network framework with an epidemiological model, thereby delivering an integrated policy tool that takes sectoral and spatial heterogeneity into account when computing both economic costs and localised disease dynamics, given commuting and workplace contact rates under particular lockdown scenarios. This tool would allow a refinement of optimal policy solutions: given an $R_t$ target in any given region, what is the optimal lockdown strategy ensuring that such targets are met at a minimum economic cost?

We conclude by discussing three policy questions that can additionally be addressed through this network methodology. First, given the nature of supply chains spanning the entire world, the effectiveness of the existing UK strategy will depend on the policies that other countries implement, in particular, those that are tightly connected to UK in the production process and consumption. Extending the production network analysis to global supply chains allows the government to identify how different phases in the contagion process that countries may experience have an impact on UK production. The analysis in Bonadio, Huo, Levchenko, and Pandalai-Nayar (2020) presents a first step in this direction and concludes that, across countries, about one third of GDP contraction during the pandemic derives from the global supply chain disruptions generated by lockdowns occurring abroad.

Second, the UK government is already injecting an unprecedented amount of money into the economy. Injections are needed to support households, cushion unemployment, avoid a prolonged loss of revenue leading to cascading failures or seizures in production, and support health of the financial network. However, it is only by targeting these injections that economic feedbacks are generated. Further, the limited fiscal government capacity implies that subsidisation of certain economic sectors should be financed by taxing other sectors. The network approach allows us to tackle this question and highlight the sectors that should be subsidised and the sectors that should finance such subsidies.17

Third, the current crisis has brought to the forefront the need to monitor and design supply chains that are responsive to shocks. Indeed, shortages of specific goods and supply chain disruptions (from ventilators to flour) are a standout feature of the past few months. How can policymakers keep key supply chains functioning? Which firms are essential for meeting demand of key goods and services in a crisis? Answers to these questions require substantially more granular datasets involving firm-to-firm transactions. This would enable researchers and policymakers to map out firm-level supply chains and apply emerging network-based insights on how to locate and safeguard key supply chains. Relative to other countries, the UK is currently lagging in this area, chiefly because of the lack of such granular data. Nevertheless, by working with payment systems operators (and the ONS), it would be possible to put together this data infrastructure, and therefore enable real-time measurement and policy interventions that could avoid key supply chain disruptions.18

5. Trade-offs Between Economic and Health Risks When Considering the Lockdown Release Date

Some of the most important decisions regarding lockdowns have to do with timing. When should the lockdown be eased? At what speed and to what extent should the lockdown be eased? How should these decisions depend on the state of the epidemic? At the time of writing, the UK has been removing lockdown restrictions for some time and is considering whether to take additional steps or to reverse previous ones. To try to answer such questions, economists have considered various reopening scenarios through the lens of integrated macroeconomic and epidemiological models that we have already discussed in Section 1. Such an integrated perspective is important when considering these questions because the interaction of epidemiological and macroeconomic dynamics means that such timing choices can have subtle and non-linear, or even non-monotone effects.

A key cautionary lesson is that a tight lockdown that is released too quickly or too fully would probably lead to adverse outcomes in terms of both lives and livelihoods. To be precise, too quickly or too fully here means relaxing the lockdown without sufficient regard for the state of the pandemic, the capacity of the health care system, and epidemiological markers such as the effective reproduction number. In terms of the policy frontier introduced in Figure 1, an abrupt reopening strategy risks yielding a point inside this frontier, meaning that it is dominated by other policy options.

The rationale is simple: an abrupt and premature lockdown exit would lead to a second wave of infections that would bring with it both a higher death toll and additional costs for the economy.19 One reason to believe that the economic consequences of such a strategy would probably be dire is the evidence that perceptions about risk of infection lead to voluntary physical distancing, so that a second wave would lead to falling economic activity even in the absence of a renewed lockdown. We have presented such evidence in Section 2 where we showed that UK, Denmark, and Sweden consumer spending declined already before the introduction of either physical distancing policies or lockdown measures (see Figures 2 and 3), consistent with the idea that fear of infections and uncertainty may be holding back consumption over and above any direct effect due to the lockdown per se.

Given this evidence, a possible consequence of a prematurely-relaxed lockdown would not only be an elevated death toll but also a double-dip recession: the first dip, which the UK has already experienced, was due to the initial lockdown; the second dip would be due to a second wave of infections and the resulting effect on economic activity. As already mentioned, the overall result would be adverse outcomes in terms of both lives and livelihoods (“a point inside the frontier”).

Through the lens of integrated macroeconomic and epidemiological models, there are other policy options that are probably preferable to an abrupt lockdown exit.20 One such option is a cautious reopening strategy that aims to keep the effective reproduction number below one (or at least in the vicinity of one) and the health care system below capacity while methods for managing the epidemic improve, e.g. by means of a potential vaccine or better disease treatment methods. Depending on assumptions about the effectiveness of relatively cheap individual-level prevention measures (such as improved personal hygiene and the wearing of face masks/coverings), these models predict that it may be possible to achieve this aim with targeted lockdown measures in place like those discussed in Sections 3 and 4. This strategy then dominates a fast and complete lockdown exit in the sense that it results in an overall welfare cost that is roughly similar but saves a larger number of lives.21 The situation can be improved further by coupling such a cautious lockdown exit strategy with other targeted approaches that we discuss elsewhere in this report, such as work rotation, and TTI schemes; in short, other schemes that expand the policy frontier and are thus more effective than indiscriminate lockdowns.

6. The Pandemic and the Labour Market

The pandemic has brought about an unprecedented labour market shock. The objective of many emergency policies has been to enable otherwise viable businesses to survive and to prevent inefficient layoffs by easing liquidity constraints and subsidising wages.22 In principle, this should enable a faster return to “normal” as restrictions are lifted. However, labour market strategy should be sensitive to the persistence of the crisis and the likelihood of further waves of infection; much of the current approach is premised on the assumption that this shock is temporary.

Workplace testing and preventing infections at work are key elements of any strategy to open up the economy. Many workers are continuing to work while sick with (mild) coronavirus symptoms (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020c)). Workers without sick pay beyond the statutory minimum are especially reluctant to return to work from furlough (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020c)). There is some adaptation to work from home, but this is occurring slowly and unequally across different occupations and industries (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020b)).

Coordination between the end/reform of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) and changed school schedules requires careful consideration. Mothers have been 10 percentage points more likely than fathers to have initiated the decision to be furloughed (as opposed to it being fully or mostly the employers’ decision) but there is no such gender gap amongst childless workers (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020c)). Women with children find it more difficult to be productive at home (Adams-Prassl (2020)). The crisis has exacerbated gender inequality in the labour market and mothers have taken on more of the extra childcare duties (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020a); Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020b); Andrew et al. (2020)). Innovative strategies to enable worker-led flexibility, such as the right to work from home and to request flexible scheduling, for facilitating parents to work in the face of disrupted childcare schedules are crucial.

What do we know?

COVID-19 is exacerbating existing labour market inequalities. Women, ethnic minorities, those with less education, workers on low incomes, and those in insecure work arrangements have been more likely to lose their job or suffer falls in earnings even if they have remained employed (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020a); Blundell, Costa Dias, Joyce, and Xi (2020); Benzeval et al. (2020); Joyce and Xu (2020)).

The government support package has so far provided an effective safety net for eligible workers and prevented even higher job losses. However, there is evidence of considerable moral hazard within the system. The majority of furloughed workers reported positive work hours when this was not permitted by the policy. In particular, furloughed workers who had their salary topped up by their employer reported working more hours. A fifth of furloughed employees surveyed by the COVID Inequality Project report being asked to work by their employer in violation of the terms of the scheme.23 This is particularly prevalent in occupations where it is easier to work from home. For example, 45% of furloughed employees working in ‘Computer and mathematical’ occupations have been asked to work while on furlough, while the corresponding share for ‘Transportation and material moving’ is 2%. Further, workers on insecure contracts24 have been more likely to be furloughed. These workers also anticipate a much higher likelihood of eventually losing their jobs. Therefore, the design of the furlough scheme needs further thinking to make it more supportive for the workers and efficient for the UK government.

There is some adaptation to work from home, but this is occurring slowly and unequally across different occupations and industries. The share of tasks that workers reported as being feasible to do from home increased between March and May (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020b)). This increase was mainly driven by an increase within occupations in which many workers were already capable of doing all tasks from home. However, within almost all occupations there is some portion of jobs that can be done from home. Understanding what drives differences in the ability to work from home across workers and firms is important for understanding what policies could be used to encourage working from home for a wider set of jobs.

Returning to work outside the home brings more opportunities for exposure to and transmission of the virus. 50% of workers continue to report positive work hours outside the home while experiencing mild coronavirus symptoms (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020c)). While the majority of furloughed workers would prefer to return to work even at 80% of their usual pay, workers without sick pay are less likely to support a return to work even when controlling for detailed job characteristics (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020b)).

Women have been hit harder economically. This is not only because men and women tend to work in different occupations and industries. Even after controlling for occupation and industry, women are significantly more likely to have lost their job or be furloughed (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020a); Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020b); Andrew et al. (2020)). Amongst those furloughed, women are less likely to have had their wage topped up after controlling for occupation and industry (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020c)). While men with children have increased the amount of childcare they do on a typical working day, the increase for women has been even larger. There must be a risk that this inhibits work and career progression for mothers. While part of the impact has already materialised in the short run, the potential for long-run scars in careers is large.

What does this suggest about strategies for opening-up the economy?

That a significant proportion of individuals have continued to work outside the home while experiencing cold-like symptoms is a public health hazard. Workplace testing should be incentivised to catch outbreaks quickly. Occupations where workers frequently come into physical contact with others should be prioritised; workers in these high-contact occupations are also less likely to have access to additional sick pay beyond the statutory minimum (Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, and Rauh (2020c)). An effective public health strategy and economic recovery are complements, and not in conflict with one another.

More research is needed into the strategies that firms and workers are employing to facilitate working from home. There is wide dispersion in the amount of work that people report being able to do from home, even within the same occupation and industries. The previous all-or-nothing nature of the CJRS scheme could have contributed to the relatively small changes in the ability to work from home in many occupations; why invest in new technologies or ways of working if none of your workers are allowed to work? For this reason (and others), the shift to “flexible furloughing”, where part-time work is permitted, is a positive policy shift. Moral hazard in the current system also suggests that revenue or production audits could speed up the return to work for those who can do so from home.

The prospect of further waves of infection and continued physical distancing measures in some form suggest that the impact of the pandemic will persist. This is important because arguments in favour of subsidising short-time work assume that the economic shock in question is temporary. Supporting firms that are not able to adapt to physical distancing measures in the medium term prevents the reallocation of workers and resources to activities that can continue in the “new normal” (Barrero, Bloom, and Davis (2020)). That workers on insecure contracts are more likely to be furloughed is suggestive that the furloughing scheme may simply be delaying unemployment. Indeed, furloughed workers are much more likely to fear losing their jobs; they report a 15% higher likelihood of losing their job before August than non-furloughed employees.

While the persistence of the shock limits the desirability of further extensions to the CJRS, the timing of the removal of CJRS and schools being reopened must be carefully considered to prevent a further deterioration in parents’, and in particular, women’s career prospects. Women have been hit harder economically and have picked up a higher proportion of extra childcare duties. Initiatives to support worker-led flexible schedules and working from home to provide more opportunities for women to remain in the labour force while childcare and school times are disrupted, are crucial.

7. Economic Issues in Physical Distancing

Estimating the impact of physical distancing policies on firm-level productivity

Physical distancing and the augmented health and safety measures–including minimum distance requirements such as the 2 meters rule–have been lauded as important drivers of the recent reduction in COVID-19 cases in many countries that adopted stringent measures. And there appear to have been falls in infection rates following such measures being put in place. The economic impact that physical distancing may have will probably vary considerably across firms and even across establishments within the same firm. There are multiple factors, including sectoral heterogeneous ability of firms to encourage work from home, that generate this kind of variation along with the physical layout of the space, e.g. the extent to which enclosed spaces can be ventilated.

There is little prior literature that has studied the interplay between physical space as a factor of production and productivity. And, there seems to be huge dispersion in the extent to which space may be a constraining factor in production. Figure 7 below presents an estimate of the average space per member of kitchen staff across 46,912 kitchens located in physical premises in English and Welsh hospitality businesses (restaurants and hotels). Across such businesses, the average physical space available in rooms designated as “kitchens” for kitchen staff members or cooks ranges from less than 1.8 square meters in the lower quintile to more than 3.9 square meters in the upper quintile in the distribution across districts. Naturally, we would expect this variation to be even more significant across establishments within districts.

Figure 7: Estimate of average space per kitchen staff member across English and Welsh Local Authority Districts.

Physical distancing requirements, such as 2 meters rule, make it virtually impossible for some establishments to operate. Others might have to significantly downsize their operations in order to be able to maintain physical distancing in the workplace.

Understanding the economic impact that physical distancing can have is imperative to help shape our understanding of the underlying policy trade-offs. The importance that physical distancing in the workplace has in COVID-19 transmission may be quite large. To illustrate, Table 1 examines the statistical relationship between the COVID-19 death rate (DV) and a measure of density in the workplace using variation across local authorities. It suggests that in the months of March and April, COVID-19 mortality rates across English and Welsh districts were notably higher in districts that have noticeably less average space per kitchen worker–a proxy for space use in production as a whole. However, there is no statistically significant correlation in May which may be due to the lockdown and physical distancing measures having become more effective.

Table 1: The statistical relationship between district-specific monthly COVID-19 mortality rate estimates and a measure of density in the workplace. Table presents the conditional and unconditional correlation between a measure of density in the workplace. This is studied for cooks and kitchen helpers. The amount of space available in a district is the total floor space in M2 available in rooms labeled as “kitchens” in physical premises classified as providing Hospitality services in the VOA lists. The number of kitchen staff is imputed from BRES employment data in Hospitality and Accommodation services along with a detailed occupation to industry mapping. The relationship with the ONS estimate of the age-standardized COVID-19 death rate disappears once the lockdown became effective.

| DV: Covid death rate in ... | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| without controls | Region fixed effects | |||||

| DV: | March | April | May | March | April | May |

| Avg M2 per kitchen staff | -2.971* | -2.810* | 1.898 | -2.642* | -4.302* | 0.738 |

| (1.519) | (2.278) | (2.605) | (1.411) | (2.345) | (2.651) | |

| Mean of DV | 67.9 | 140 | 98.5 | 67.9 | 140 | 98.5 |